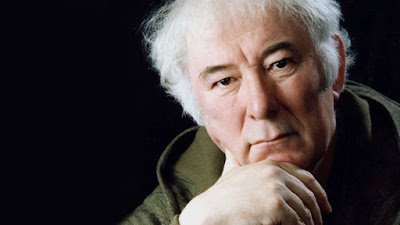

Seamus Heaney wasn’t anti-Catholic, but he saw Irish Catholicism as a thing of the past

Introduction to this post

What a wet week it has been here in London. A soggy August gave way to a sodden September 2017. Popping around London and hearing the announcements on loudspeakers in the tube train stations advising customers to be careful because 'inclement weather' makes the floors of the stations slippy - brings my mind back to Septembers in Ireland when it rained all the time and of walking to school in the wind-driven rain that always found a way into your shoes and schoolbag and of having to sit through classes in wet, clammy clothes.

A more visceral memory still is of one I used to have all through school of preparing to study Seamus Heaney and then as a 20 year-old preparing to be taught by him. I don't recall it as a merry mindfulness, rather of being mentally muzzled: you had to praise and praise the poetry of Heaney, no criticism of his poems was ever tolerated. Almost like your checklist for school or college was, 'lunch, homework and that mental note to self never to say anything critical of Seamus Heaney's poems'.

Poetry was always my best subject and so perhaps I feel this censorship imposed on us by our teachers and professors more keenly. But I can't help but wonder if a whole generation of Irish schoolchildren were deliberately indoctrinated into idolising a poet who situated Catholicism as a thing of the past - and if this was not part and parcel of our cultural conditioning as a whole.

Heaney died four years ago and after his sad passing I wrote this piece for The Catholic Herald -

When I was taking my university degree in English Literature and Education, the most reckless students that I

knew took large quantities of cocaine and drove while drunk. But there

was one dangerous exploit that they avoided: they never uttered a word

against Seamus Heaney, either in their essays or to the faces of our

professors. To do so was to risk disapproval of a deadly kind. You did

not want to risk your university degree for comments against the man

treated like the Messiah of Irish literature.

Heaney was one of our guest lecturers, and one day, I plucked up the courage to ask him, “What advice would you give new writers writing in a postmodern climate?” Heaney looked at me with a perplexed expression and said in front of a packed lecture hall, “Postmodernism? That’s a fashion of literary criticism.” He waved his hands from side to side and dismissed my question. None of the English literature faculty who had staked their careers on postmodernism interjected. They smiled and simpered under his every word.

It begs the question: why was Heaney so adored? Even if his poetry lifts you to new heights, as it does me, the absolute adulation is suspect. It mystifies many why Heaney, an Irish Catholic, who wrote about Catholicism, was continuously exalted by the liberal, secular elite.

What a wet week it has been here in London. A soggy August gave way to a sodden September 2017. Popping around London and hearing the announcements on loudspeakers in the tube train stations advising customers to be careful because 'inclement weather' makes the floors of the stations slippy - brings my mind back to Septembers in Ireland when it rained all the time and of walking to school in the wind-driven rain that always found a way into your shoes and schoolbag and of having to sit through classes in wet, clammy clothes.

A more visceral memory still is of one I used to have all through school of preparing to study Seamus Heaney and then as a 20 year-old preparing to be taught by him. I don't recall it as a merry mindfulness, rather of being mentally muzzled: you had to praise and praise the poetry of Heaney, no criticism of his poems was ever tolerated. Almost like your checklist for school or college was, 'lunch, homework and that mental note to self never to say anything critical of Seamus Heaney's poems'.

Poetry was always my best subject and so perhaps I feel this censorship imposed on us by our teachers and professors more keenly. But I can't help but wonder if a whole generation of Irish schoolchildren were deliberately indoctrinated into idolising a poet who situated Catholicism as a thing of the past - and if this was not part and parcel of our cultural conditioning as a whole.

Heaney died four years ago and after his sad passing I wrote this piece for The Catholic Herald -

Heaney was one of our guest lecturers, and one day, I plucked up the courage to ask him, “What advice would you give new writers writing in a postmodern climate?” Heaney looked at me with a perplexed expression and said in front of a packed lecture hall, “Postmodernism? That’s a fashion of literary criticism.” He waved his hands from side to side and dismissed my question. None of the English literature faculty who had staked their careers on postmodernism interjected. They smiled and simpered under his every word.

It begs the question: why was Heaney so adored? Even if his poetry lifts you to new heights, as it does me, the absolute adulation is suspect. It mystifies many why Heaney, an Irish Catholic, who wrote about Catholicism, was continuously exalted by the liberal, secular elite.

Dare I unravel the mystery: Was it because Heaney wrote as though

Catholicism was an institution that belonged to the past? Heaney’s

catalogue of poetry records the clash between new and old Ireland, the

time before electric light and the time after. But alongside gas lamps,

did Heaney relegate Catholicism as something that would recede into the

background of Irish history? Was it this approach that won him the

favour of the secular establishment?

Let us be clear, Heaney was not an anti-Catholic poet. He did not write to discourage others from the Faith. Heaney was part of the age group that came into its own in the 1960s. He painted himself as being an observer of a religion that died out with his parents’ generation.

Take the poem, When all the others were away at Mass. Heaney describes the experience of being at his mother’s deathbed. While the poet watches his mother die, the parish priest recites the prayers for the dying, but Heaney does not join in, instead he remembers his favourite memory of his mother, which was when they peeled potatoes while the rest of the family were away at Mass. The implicit message is that he would prefer to remember preparing food with her, than pray for her soul, “So, when the parish priest at her bedside went hammer and thongs at the prayers for the dying… I remembered her head bent towards my head.”

In time, it will be realised that this adulation of Heaney was the very toxin that inhibited him. Heaney was never challenged to excel beyond his great achievements, when he clearly had phenomenal talent. Not all his poems are of equal quality, and some are superior to others. There has not been a thoroughly honest comparison between Heaney and another Irish poet who lived and breathed that harsh rural, farming life. One such poet would be Patrick Kavanagh. It is telling that so few know of Patrick Kavanagh, a poet who bared his Catholic soul for everyone to see.

In our times, Kavanagh will never know Heaney’s popularity and I question if it is partly because he wrote about being inside the Faith, not outside it, and as though the Faith was a living reality?

I wrote this post for The Catholic Herald. You may visit The Catholic Herald for breaking news and fresh commentary on what's really happening in Catholicism. This post is tagged under Growing up a Millennial in Ireland and as A Practising Catholic Millennial.

Let us be clear, Heaney was not an anti-Catholic poet. He did not write to discourage others from the Faith. Heaney was part of the age group that came into its own in the 1960s. He painted himself as being an observer of a religion that died out with his parents’ generation.

Take the poem, When all the others were away at Mass. Heaney describes the experience of being at his mother’s deathbed. While the poet watches his mother die, the parish priest recites the prayers for the dying, but Heaney does not join in, instead he remembers his favourite memory of his mother, which was when they peeled potatoes while the rest of the family were away at Mass. The implicit message is that he would prefer to remember preparing food with her, than pray for her soul, “So, when the parish priest at her bedside went hammer and thongs at the prayers for the dying… I remembered her head bent towards my head.”

In time, it will be realised that this adulation of Heaney was the very toxin that inhibited him. Heaney was never challenged to excel beyond his great achievements, when he clearly had phenomenal talent. Not all his poems are of equal quality, and some are superior to others. There has not been a thoroughly honest comparison between Heaney and another Irish poet who lived and breathed that harsh rural, farming life. One such poet would be Patrick Kavanagh. It is telling that so few know of Patrick Kavanagh, a poet who bared his Catholic soul for everyone to see.

In our times, Kavanagh will never know Heaney’s popularity and I question if it is partly because he wrote about being inside the Faith, not outside it, and as though the Faith was a living reality?

I wrote this post for The Catholic Herald. You may visit The Catholic Herald for breaking news and fresh commentary on what's really happening in Catholicism. This post is tagged under Growing up a Millennial in Ireland and as A Practising Catholic Millennial.

Comments

Post a Comment